An Interview with Photo Editor Eliane Laffont

Great photo books have the power to ignite the imagination – spurring photographers and imagery enthusiasts into a passionate delirium of hope, ambition and, in some cases, a deeply resonating sense of self. There are three integral parts to a photo book; firstly, the photographer, secondly the photo editor, and thirdly, the publisher.

In an interview with Eliane Laffont, an award winning photo editor and one of the most well respected forces in the photo industry, she speaks about the new book “Photographer’s Paradise: Turbulent America 1960-1990”, a collaborative venture between her husband, photojournalist Jean-Pierre Laffont, and herself. She also describes the delicate art of photo editing, the rigorous journey of publishing a book and offers some advice for young photographers.

How did Photographer’s Paradise come about? How did the idea of the book progress?

When Jean-Pierre and I started to work on the idea of making a book, we gathered all the different boxes containing millions of slides, negatives and contact sheets that were stored in different warehouses. What came to my mind right away, is while Jean-Pierre is famous for having covered world-wide events, he is not as known for his work in the United States.

When we decided to make the book, I wanted to start on the U.S. and this is where I, as an editor, had the most fun. I could look back, rediscover, and also re-edit. For example, the photographs of the demonstration against the Vietnam War. At the time, we had syndicated the demonstration of the people in the street, but I had never edited the portraits. You know, photography during all those years has evolved, and it was interesting to see how my process of editing has also evolved. It was an extremely challenging and an intellectually stimulating process for me.

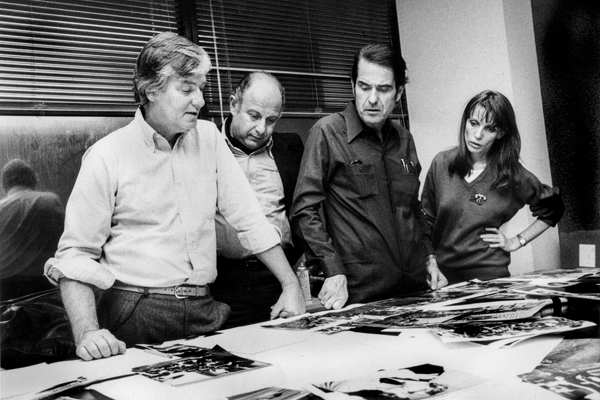

LOOK Magazine, New York City - 1978. From left to right: Regis Pagniez, art director, Paul Slade, photographer of Paris Match, Daniel Filipacchi, President of LOOK Magazine and Eliane Laffont, Director of Photography. Taken by Jean-Pierre Laffont

Could you expand on the process of editing?

It was interesting for me to edit Jean-Pierre’s work because I had to follow what he was trying to do with photography and to tell the entire story as seen through Jean-Pierre’s eyes. This project taught me how to visually build a story, similarly to how a writer constructs a story with words; there is an introduction, the development and a conclusion. So it was a very interesting editing process for me to learn.

That’s very fascinating, I think that’s the first time I have ever heard that images have been so comparable with writing.

Yes, and certainly it was the case with Jean-Pierre’s work. This why Photographer’s Paradise is more about stories, as opposed to individual photographs - I cannot think of a story that Jean-Pierre covered that he did not stay for weeks, or months at a time and that he didn’t continually develop.

So when I started to edit the work for the book, it seemed obvious to me that I had to go by story. This is how the theme of the book came about, because I went back to his stories, and I realized that he had captured the defining moments of American history, as a whole story, not just with one photograph.

Can you tell me how you became a photo editor?

In the late 60’s, I was a sales rep for the French agency Gamma. This agency represented photographers like Gilles Caron, Henri Bureau, and Raymond Depardon. These photographers would send me their raw film, I would choose between 30 – 40 images, and then take them to John Durniak, the picture editor at TIME magazine.

When I began to edit for magazines, I tried to familiarize myself, firstly, with the magazine, then, the information in the picture, and, lastly, the style of the photographer. It is important to take your time when you edit, because an editor has the ability to make or break a photographer’s future.

For young photographers, it is essential to know that there is no such thing as right and wrong – there are opinions. What is truly important is to develop your own style.

Manhattan, New York - Circa 1980. Eliane Laffont at the Sygma office, at 225 West 57st. Taken by Douglas Kirkland.

You’ve edited a few books, In the Eye of Desert Storm and the ‘Day In the Life Of’ series, and I wanted to ask, what were some of the challenges you faced while editing Photographer’s Paradise?

One of the biggest issues I had at the start was sifting through hundreds of negatives and contact sheets, and thousands of slides. Before I met the publisher Marta Hallett, the question that I had was what book were we going to do? Am I going to do the best of, or Jean-Pierre’s life as a photographer? I needed to find a theme that was going to help me as an editor.

It was when I went to see the first publisher, Marta Hallett from Glitterati Incorporated, that she gave me a clue. I don’t think she realized it – at the time, she was looking through Jean-Pierre’s photographs and she said to me, “It seems to me that to help you with the edit, you should go by decade”. Right away, that gave me the clue as to what the book was going to look like… This was when I started to realize that I was editing stories, not just photographs.

Is there anything else you would like to say about the editing process?

What I find very interesting about the process of going through Jean-Pierre’s work, is that for the book and for the gallery there are two different edits. And this is the part that I am teaching myself.

I have never worked with galleries; my background is books, newspapers and the press. I have never edited Jean-Pierre’s, or any photographer’s work, having it in mind for a gallery - now I am doing that. I have made some mistakes at the beginning, I went to see galleries and they would say that it was too “newsy”, and I would go back to the work, and think, “okay, what does that mean?” So it made me aware about what galleries need and that particular aspect of photography.

How did you deal with this? Are you getting more used to it?

I have been living with this book for a year now and from the beginning, I placed the photographs from the book on the walls of my office. I come from the generation where we would work with the art director and rather than use a computer, we would edit the magazine on a wall.

This method has stayed with me because the photographs always remain with you. You live in the middle of them. If you use a screen, you can easily and swiftly change it. They should be permanent and this how I made the edits for the galleries.

I wanted to ask you, do you have any new projects on the horizon?

When Photographer’s Paradise is published, we will have another million of slides to sift through. My next project will be another book on Jean-Pierre, and this time it will include the work in color.

Many photographers like the idea of a book, of self-publishing a book, but the editing process is one of the most complicated aspects of making a book. What would be some advice that you would give to people who are trying to self-edit and self publish their book?

My advice is, if you don’t like to edit your work, then contact a good editor. Especially, one that you know and are close to. Editing the work of a photographer is not only picking his eye but also picking his brain. Additionally, an editor must know of the photographer and also know of the story.

Did you contribute to the layout of the book? For example, who decides which photograph would be a featured as a double spread?

For me a double page is the combination of the information, the visual impact of the photograph, and the impact of the story itself. They are the best photographs of that specific story. Not every photograph, especially when you have 400 images, can be a double page, even though it is a photographers dream.

We had a discussion about which images would be double pages and which would be single pages, and of course, in the end, the book is a combination of two talents, the photographer’s and the art director’s.

Discussion is important, because without that discussion you can’t combine the best of both worlds.

Yes, it has to be a discussion, and the lines of communication have to be open. While we have been working on Photographer’s Paradise, and Glitterati have been very supportive and understanding.

Jean-Pierre is always amazed that people like his work, and for him, the main thing is to have photographed it.

Manhattan, New York, June 2013. Eliane and Jean Pierre Laffont in their studio editing the photographs for the book Photographers Paradise (Glitterati Incorporated, Fall 2014). The suitcase travelled around the world with Jean Pierre Laffont. Taken by Sam Matamoros.